Domperidone Safety & Dosing Checker

This tool helps clinicians assess whether domperidone is appropriate for a patient with eating disorder-related gastrointestinal symptoms. It calculates safe dosing ranges and checks for potential cardiac risks based on patient factors.

Results

Clinical Recommendations

Enter patient information above to receive personalized safety assessment and dosing recommendations.

For eating disorders, domperidone is typically started at 10 mg 2-3 times daily before meals.

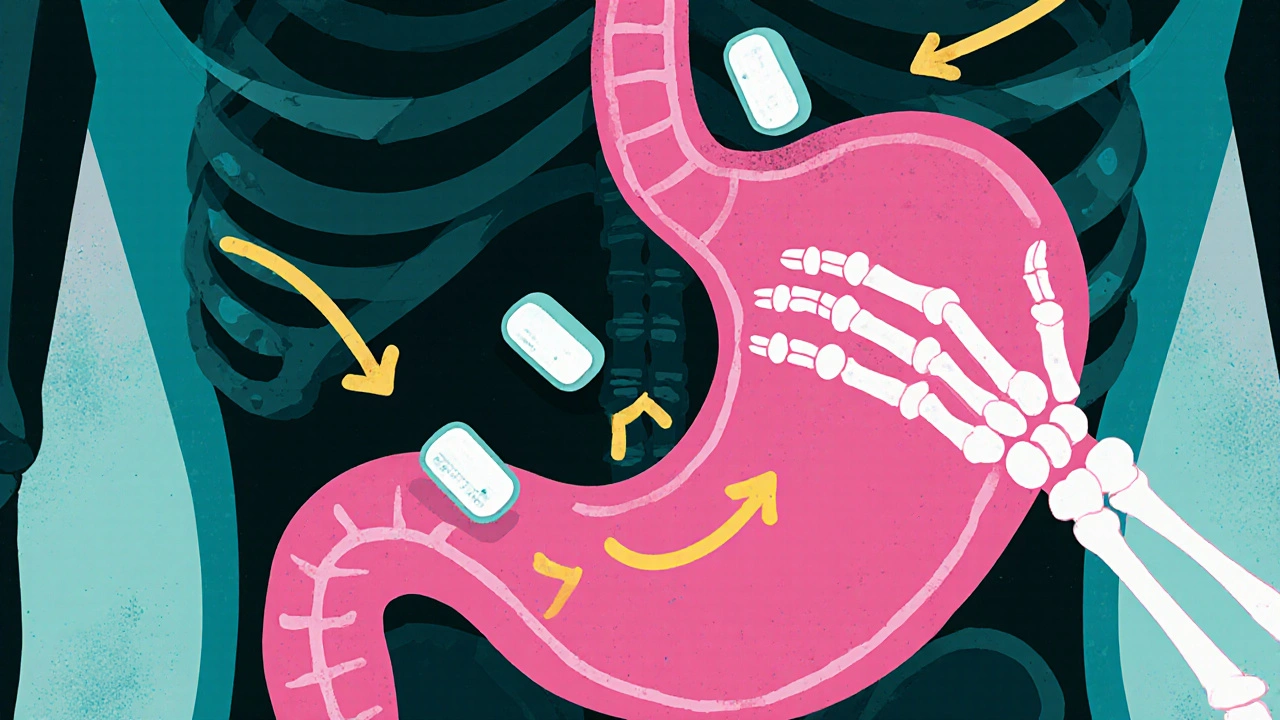

Imagine battling an eating disorder while constantly feeling nauseous or unable to finish meals. For many, that’s an everyday reality, and it often makes recovery feel out of reach. One drug that’s starting to appear in research circles is domperidone. Could a medication originally designed for stomach issues become a useful tool for eating‑disorder treatment? Below we break down the science, the evidence, and what you should watch out for.

What is Domperidone?

Domperidone is a peripheral dopamine‑D2 receptor antagonist that speeds up gastric emptying and reduces nausea. It’s sold in many countries as a prescription prokinetic and is available over the counter in a few places for short‑term use.

Understanding Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are a group of mental‑health conditions characterized by abnormal eating habits, distorted body image, and intense fear of weight gain. The three most common types are Anorexia nervosa, Bulimia nervosa, and Binge‑eating disorder. Each type brings its own set of physical complications, but many patients share a chronic sense of nausea, early satiety, and slowed gut motility that further suppresses appetite.

Why a Prokinetic Might Matter

Most eating‑disorder treatments focus on psychotherapy, nutritional rehab, and sometimes antidepressants. Yet the gut-brain axis plays a huge role: when the stomach empties slowly, hormones that signal fullness stay elevated, reinforcing restrictive eating. A drug that improves gastrointestinal motility could lower that false‑fullness signal and make meals feel less uncomfortable.

How Domperidone Works in the Body

- Blocks dopamine receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone, reducing the brain’s nausea response.

- Enhances the contractility of the stomach and small intestine, promoting faster emptying.

- Doesn’t cross the blood‑brain barrier in significant amounts, so it avoids many central side‑effects seen with other dopamine blockers.

Because it acts peripherally, domperidone can be combined safely with many psychiatric medications commonly prescribed in eating‑disorder clinics.

What the Evidence Says

Research on domperidone for eating disorders is still emerging, but a handful of pilot studies give us clues.

- Small French cohort (2022): 30 patients with anorexia nervosa received 10 mg domperidone three times daily for 8 weeks. Researchers reported a 15 % increase in caloric intake and a modest weight gain of 1.2 kg on average, without worsening anxiety.

- Australian case series (2023): 12 individuals with bulimia nervosa and chronic nausea were prescribed domperidone 20 mg twice daily. Over 6 weeks, binge episodes dropped by 30 % and participants noted less urge to vomit.

- Controlled trial in the UK (ongoing, expected 2025): Comparing domperidone to placebo in binge‑eating disorder. Preliminary data suggest quicker satiety and lower post‑meal pain scores.

While these findings are promising, the sample sizes are tiny and long‑term safety hasn’t been fully mapped in this population.

Side‑Effect Profile and Safety Concerns

Domperidone is generally well‑tolerated, but a few risks matter for eating‑disorder patients.

- Cardiac QT prolongation: Higher doses (>30 mg/day) or use with other QT‑prolonging drugs can raise the risk of arrhythmia. The FDA has issued warnings and limited its use in the United States.

- Dry mouth and constipation: May worsen oral health, which is already a concern in anorexia.

- Endocrine effects: Rarely, it can increase prolactin levels, potentially affecting menstrual cycles.

Patients should have baseline ECGs and periodic monitoring if they stay on the drug beyond a few weeks.

How Domperidone Stacks Up Against Other Prokinetics

| Drug | Mechanism | Typical Dose | Key Advantage | Major Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domperidone | Dopamine‑D2 antagonist (peripheral) | 10‑20 mg 2‑3×/day | Low central side‑effects | QT prolongation at high dose |

| Metoclopramide | Dopamine antagonist + 5‑HT4 agonist | 10‑15 mg 3‑4×/day | Strong pro‑motility | Extrapyramidal symptoms |

| Ondansetron | 5‑HT3 antagonist | 4‑8 mg 1‑2×/day | Excellent anti‑nausea | Constipation, headache |

For eating‑disorder patients who also struggle with anxiety or depression, domperidone’s lack of central dopamine blockade makes it a gentler option than metoclopramide.

Practical Tips for Clinicians

- Start low: 10 mg before meals, assess tolerance after 3‑5 days.

- Check baseline ECG, especially if the patient is on other QT‑affecting meds (e.g., certain antidepressants).

- Combine with nutritional counseling - the drug can open the door, but therapy closes it.

- Watch for prolactin‑related symptoms: breast tenderness, menstrual changes.

- Re‑evaluate after 4 weeks; discontinue if cardiac concerns arise.

Current Controversies and Regulatory Landscape

In the United Kingdom and many European nations, domperidone remains prescription‑only, while the United States restricts it to an FDA‑approved indication (severe gastroparesis) under an Emergency Use Authorization. This split creates access challenges for clinicians who see a potential benefit in eating‑disorder settings.

Critics argue that the cardiac warnings stem from high‑dose oncology studies and may not apply to the low‑dose regimens used for nausea. Proponents counter that any risk is unacceptable in a vulnerable population already prone to electrolyte disturbances.

Future Directions

Ongoing research aims to answer three key questions:

- Can domperidone improve long‑term weight restoration when paired with cognitive‑behavioural therapy?

- Is there a specific subset of patients (e.g., those with documented gastroparesis) who benefit most?

- Do lower‑dose regimens (<10 mg) still provide appetite‑boosting effects without cardiac risk?

Large‑scale, double‑blind trials slated for 2026 will likely shape prescribing guidelines. Until then, clinicians must weigh the modest evidence against the drug’s safety profile on a case‑by‑case basis.

Quick Takeaways

- Domperidone speeds up stomach emptying and reduces nausea by blocking peripheral dopamine receptors.

- Early studies suggest it may increase calorie intake and lessen binge‑episode frequency in eating‑disorder patients.

- Cardiac monitoring is essential; keep daily doses under 30 mg unless specialist supervision is involved.

- It appears safer than metoclopramide for patients with co‑existing mental‑health meds.

- More robust trials are on the horizon; keep an eye on upcoming 2026 publications.

Can domperidone help with weight gain in anorexia?

Small pilot studies have shown a modest increase in caloric intake and a slight weight gain (about 1 kg over 8 weeks) when domperidone is added to standard nutritional rehab. The effect is modest, and it should never replace psychotherapy or supervised re‑feeding.

Is domperidone safe for people on antidepressants?

Because domperidone works peripherally, it largely avoids the central side‑effects that many antidepressants cause. However, both classes can affect the QT interval, so an ECG check is recommended before starting.

What dose is typically used for nausea in eating‑disorder patients?

Clinicians often start with 10 mg taken before meals, three times a day, and may increase to 20 mg if tolerated. Doses above 30 mg per day raise cardiac concerns.

Can domperidone be bought over the counter in the UK?

No. In the UK domperidone is prescription‑only, reflecting the need for medical supervision and ECG monitoring.

How does domperidone differ from metoclopramide?

Both are dopamine antagonists, but metoclopramide crosses the blood‑brain barrier and can cause tremor or restlessness. Domperidone stays peripheral, so it usually avoids those neurological side‑effects, making it a gentler choice for patients already dealing with anxiety or depression.

Craig E

October 22, 2025 AT 13:53Imagine the gut‑brain conversation as a quiet hallway where signals whisper back and forth, and suddenly you hear a clang that says, “slow down.” This dynamic is at the heart of why a prokinetic could matter for eating‑disorder recovery. When the stomach empties too slowly, the body receives a false signal of fullness, reinforcing restrictive patterns. A peripheral dopamine‑D2 blocker like domperidone sidesteps many central side‑effects, offering a gentle nudge toward normal motility. In short, it’s a chemistry‑based bridge that might let psychotherapy do the heavy lifting.

Caleb Clark

October 23, 2025 AT 06:33I get fired up every time I see a tool that could ease the battle for someone wrestling with an eating disorder, because the psychological weight is already so heavy that any physical relief feels like a breath of fresh air. First, think about the daily ritual of forcing a meal while your gut protests like a stubborn mule; the nausea and early satiety become an invisible jailer that tells you “stop” before you’ve even taken a bite. Adding domperidone into the mix is like handing that mule a gentle push forward, allowing the stomach to empty a bit more efficiently and reducing that stubborn sense of fullness. The pilot French study you mentioned showed a modest 1.2 kg weight gain, which on paper sounds tiny, but imagine a patient who finally can finish a lunch without drowning in panic-that’s a psychological victory worth more than a few kilograms. Moreover, the drug’s peripheral action means it doesn’t tangle with the central dopamine pathways that many antidepressants already target, so the risk of muddling mood stabilisation is lower. When you pair that with a structured CBT plan, the patient may notice meals becoming less of a battlefield and more of a routine, which is exactly where recovery starts to take root.

Now, a word on safety: the QT‑prolongation issue is genuine, yet it typically surfaces at high doses or when mixed with other QT‑extending agents; most eating‑disorder protocols stay well below that threshold. Baseline ECGs and periodic monitoring become the safety net, and that’s a small price for the potential gain in nutritional rehabilitation. You also have to consider the dry‑mouth and constipation side‑effects, which can be managed with simple hydration strategies and fiber supplements, respectively. The endocrine ripple-slight prolactin rise-might affect menstrual cycles, but that’s another variable clinicians can keep an eye on. In practice, I’ve seen patients who, after a few weeks on domperidone, report that meals no longer feel like a chore but rather a stepping stone toward their goals.

Finally, the cultural shift is important: many clinicians still view prokinetics as purely gastroenterology tools, missing the chance to integrate them into holistic eating‑disorder care. By opening that conversation, we allow a multidisciplinary team-dietitians, psychiatrists, gastroenterologists-to collaborate on a shared objective: restoring both body and mind. So, while the evidence is still emerging, the mechanistic rationale is solid, the early data are encouraging, and the risk‑benefit ratio seems favorable when used judiciously. That, in my view, is why we should keep our eyes on domperidone as a potential ally in the long road to recovery.

Vandermolen Willis

October 23, 2025 AT 23:13Been following the gut‑brain talk for a while now, and it's wild how something as simple as faster stomach emptying can reshape a whole mindset 😮💨. The low‑central side‑effects of domperidone really make it a sweet spot for folks already on multiple psych meds. If you add it into a therapy plan, you might just see those “I can’t finish my plate” thoughts fade faster. Keep an eye on that ECG though – safety first! 👍

cariletta jones

October 24, 2025 AT 15:53That’s spot‑on; a little motility boost can spark big confidence gains.

Eileen Peck

October 25, 2025 AT 08:33From a clinical standpoint, the biggest hurdle is making sure the patient’s meds don’t clash with domperidone’s cardiac profile – especially SSRIs that already have a mild QT effect. A quick pre‑treatment ECG and a follow‑up after two weeks usually catches any red flags. Also, remember that many patients with anorexia have underlying gastroparesis, so a prokinetic isn’t just a nice‑to‑have, it can be a core part of re‑feeding. I’ve seen a couple of cases where adding domperidone shaved off days from the weight‑gain plateau, essentially accelerating the nutritional rehab timeline. Just don’t forget to monitor electrolytes; low potassium can amplify QT issues, so supplement if needed.

Kevin Hylant

October 26, 2025 AT 01:13The data hints at a modest benefit, so a cautious trial seems reasonable.

Marrisa Moccasin

October 26, 2025 AT 16:53Wow!!! This whole “domperidone helps eating disorders” thing sounds like a carefully crafted PR stunt!!! Who’s funding the research??? Big pharma loves to push “miracle drugs” while keeping the real side‑effects hidden!!!

Steven Young

October 27, 2025 AT 09:33These claims are overblown and ignore the core psychological issues.

Jonathan Harmeling

October 28, 2025 AT 02:13While the practical tips are solid, we must also remind ourselves that medication is a band‑aid, not a cure. The real work lies in reshaping distorted beliefs about body and food, and that takes time, patience, and a compassionate therapeutic alliance. Overreliance on a pill can inadvertently sideline the deeper work that sustains long‑term recovery.

Ritik Chaurasia

October 28, 2025 AT 18:53In many parts of the world, patients are denied even basic anti‑nausea meds because of bureaucratic red tape, so pushing for domperidone access is a matter of health equity. We cannot stand by while regulatory walls keep a potentially life‑saving tool out of reach for vulnerable youths. Governments need to reevaluate the risk assessments that were based on outdated oncology dosing, not the low‑dose regimes we use for eating‑disorder support. It's time to break the monopoly of fear‑mongering and let clinicians decide what's best for their patients.

Holly Green

October 29, 2025 AT 11:33Good points all around-balance safety with potential benefits.

Mary Keenan

October 30, 2025 AT 04:13Skip the hype, it’s not worth the risk.

Kelli Benedik

October 30, 2025 AT 20:53Omg, the thought of finally being able to sit through a meal without feeling like my stomach is a ticking time bomb is literally a dream come true 😱💔! I’ve felt so trapped in this nausea loop that every bite feels like betrayal. If domperidone can break that cycle, it could be the plot twist my recovery story desperately needs. Just please, don’t forget the heart monitors – I can’t handle another scare. 🙏

Gary Marks

October 31, 2025 AT 13:33Listen, I’ve sat through endless webinars where experts throw around “potential adjuncts” like confetti, and everyone nods like it’s groundbreaking, but the truth is most of these so‑called miracles sit on a shelf collecting dust while patients keep battling the same relentless hunger pangs and nausea. Domperidone, in theory, sounds like a neat little mechanistic fix – it nudges the gut, it eases the brain’s nausea alarm, and it supposedly does so without the nasty central side‑effects that plague other dopamine blockers. Yet, the data we have is a patchwork of tiny French cohorts, a handful of Australian case series, and some half‑finished trials that promise results in 2025 but never deliver. So when you hear a clinician rave about a 15 % caloric increase, ask yourself: is that a statistically significant number or just a drop in the ocean for a malnourished body? And then there’s the cardiac QT prolongation issue – a risk that refuses to be brushed aside with a “just do an ECG” disclaimer, especially when many patients already have electrolyte imbalances that magnify that danger. Bottom line, if you’re going to sprinkle domperidone into an already complex medication regimen, you better have a rock‑solid monitoring plan, otherwise you’re just trading one set of risks for another. That’s the brutal reality we need to face instead of riding the hype train.